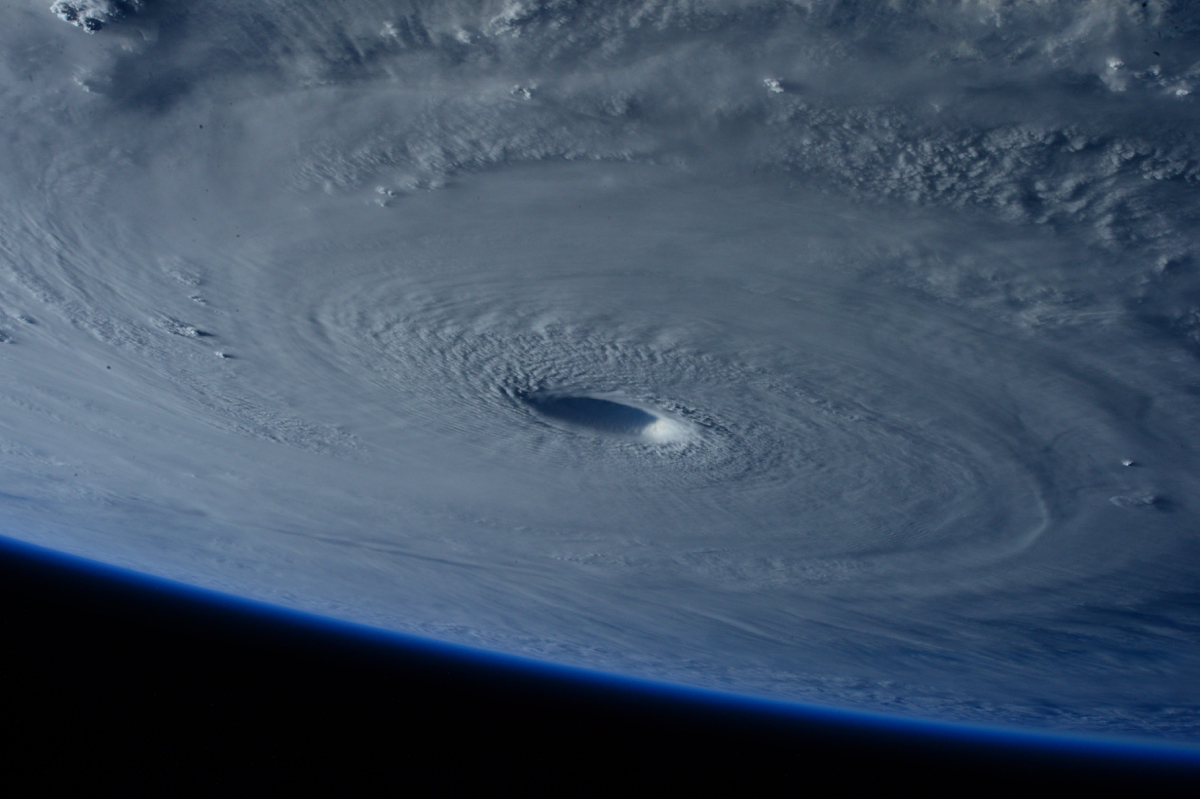

Image Courtesy of NASA

The Day the Storm Ends

by Jenny Maloney

The Great Red Spot has glared out at the universe for centuries. Rachel glares back.

Now: The near dead spaceship uses the last of its fuel to keep pace with Jupiter’s rotation. The white and purple and maroon clouds swirl into the pressure system like water flooding a tidepool. The maelstrom is so large it fills the observation window. So large it would swallow Earth twice over. So large it swallows her.

Rachel floats above the Great Red Spot. The swirling monster below her is echoed by the alarm lights flashing on her console. FAILURE. Thanks machine. The flashes remind her of leaks. Instead of water, it is the storm sneaking in.

They will hail her as a hero, despite her failure. Hovering here, the cold creeping. Closer than anyone has ever been to the Great Red Spot.

Then: Her first view of the great storm was through a telescope propped on a glacier in Prince William Sound, twenty years before the last glaciers melted away. Clear night. CeleStellar N17 telescope. Her father, smelling of Altoids and stale coffee leaning in beside her. The Great Red Spot, he told her, was discovered 271 years ago by Samuel Heinrich Schwabe. Though her father believed Cassini saw it raging centuries before that.

Now: The storm rages at her feet. Schwabe and Cassini would be jealous.

Rachel sees the changes with her naked eye two hours after she accepts she will never get her ship going again. When the FAILURE was new, the storm had filled the window — an entire wall of her ship, the Iovis, from edge to edge. Now a border of eddying white and gray and blue and rust-colored clouds edge into her view, like petals blown by rough winds. She is drifting toward the storm, so it should grow larger as her orbit decays, not smaller. Yet here it is — shrinking.

Rachel pushes toward the console. It still blinks FAILURE. But the instruments still measure. The comm still works, despite the current sorrowful silence. There is no sound except her own breathing. She focuses on the weather systems. The wind speeds at the edge of the storm have dropped to an Earth-level strong 170 mph.

Then: On her father’s ship, Clara, named for her mother. Her father handed her binoculars and pointed at the horizon. A wall of giant gray clouds hovered over the ocean surface. She felt the temperature drop through her jacket. She fought to keep her balance. The boat rocked, buffeted by choppy black waves. The Coast Guard warning blared from the radio. “Look at it,” he said. “Look at that monster.”

That monster, Alaska Hurricane Gretel, swept across the coast of Alaska. The tsunami killed a fifth of the Sitka, Alaska, population. And her mother. Rachel watched the storm front through her binoculars, watched the sky and sea join forces, watched helpless and wet.

The storm was not predicted to move that far north. Her mother told her to go with her father, enjoy a day on the ocean. She’d tied the laces on Rachel’s boots.

Her boots stayed tied the whole time.

Where Sitka Harbor used to be, the houses and buildings were shattering into clumps of wood and glass. Things floated in the water: roof shingles, wooden planks, the “Be right back” sign which used to hang on one of the Seaplane Base doors, a bloated copy of Stephen King’s Everything’s Eventual, a 35 mph speed limit sign, a North Star Rentacar banner. The land moved to the sea and the sea to the land. Pink salmon, Dolly Varden char, cutthroat trout lay stranded on the new waterfront.

Watching the fish unable to breathe — Rachel understood suffocation — drowning — to be the worst death. Rachel refused to eat fish after that day.

They lived on the boat. And Rachel never went without binoculars. Always searched the horizon. Learned different cloud patterns. Cumulus, cumulonimbus, nimbostratus, cirrus. She used the binoculars to study storms on Earth. She used the telescope to study storms on other planets. Rachel hunted the storms before they could hunt her.

The ocean sky was clear at night — free from land’s light pollution. Rachel found Venus and Mars and Saturn. But none of the other celestial bodies held her interest like Jupiter.

Now: Outside her window, the Great Red Spot continues to break up. Rachel measures the atmospheric shifts. Cracks show in the vortex, the way clear blue skies, like mirages, peek through after thunderstorms.

Static fills the small cabin. Strangely, the white noise melds and swirls with the storm below her. As the red breaks, the static churns. Voices far away are trying to be heard. They’re broadcasting from the Houston base — named for that long-gone city — on Europa.

A voice breaks through the static.

“Rachel. Rachel, are you there? Copy? Am I through?” A blur of angry static answers him. “Rachel, it’s Dad. Can you hear me out there? Talk to me, kiddo.”

She reaches out to turn the comm off — half-thinking she’s imagining her father’s voice. Rachel’s not about to forgive him for misjudging the skies that day, imminent death now or not.

“Answer me. Now.”

Then: His first move during the storm that killed her mother was to force a life jacket on Rachel. Then he’d hollered orders at her. Shut off the fuel lines. Seal off the windows while he drops anchor. She’d done everything he said.

By the tenth hour, her arms were lead. He told her to take the wheel and hold steady into the winds. She cried. “Just fucking do what I tell you.” He yelled, but only to be heard over the screaming wind. He expected her to do it. So she cried and did what he told her. She took the wheel. It shuddered and vibrated. Her teeth rattled.

Her father grew up on boats. Knew all the nooks and crannies. Understood what they could withstand. He knew his ship but misjudged the storm. A rogue wave pitched the boat. Rachel watched it throw him. He hit his head.

Rachel did what he told her. Kept everything as steady as she could. By the end, she was soaking wet. Her clothes felt as heavy as the ocean itself.

After her father hit his head, there was blood. It had swirled around in puddles of water flooding the bridge. The pattern looked like the Great Red Spot now: swirling and somehow dissolving. He lay face down.

Without letting go of the wheel, she’d kicked him onto his back so he wouldn’t drown. Then she fucking did what he told her to do.

Now: Below her, the spot is melting away. Now five, now twelve, smaller dots of itself. Pieces breaking into smaller pieces, and then smaller again, resembling the loops and whorls of the String of Pearls nearby.

Rachel ignores her father and his ghostly voice. According to her instruments — what’s left of them — what she observes in her window is accurate: the centuries-old storm is ending.

“Rachel, pick up the comm.”

Just fucking do what I tell you. Watching the storm fade, she thinks it’s strange that a storm breaking should look so identical from above as below.

Then: Patches of blue which looked so light it could be mistaken for another layer of cloud. She’d held onto the wheel so tight and stared out the window so long she no longer felt her body. Slowly, the waves quieted, the wind faded, and a strange silence filled the blue space between the clouds.

Now: The dissipating red gasses fade and patches of other, still-unknown elements appear. How lucky she is. The last thing she will witness is the death of the greatest storm in the solar system.

Rachel ignores the comm. She focuses instead on wind speed, directions. If her calculations are correct, the storm will burn out in twelve hours, maybe less. She has enough fuel to keep pace for about ten of those hours. Enough oxygen in the cabin for eight of those hours. She can suit up toward the end of the eight hours to buy herself a little more time. Floating here, she feels the age of the storm. Maybe Cassini started this observation. She will end it.

Her notebook is filled with sketches, weather documentation, notes about patterns and chemical compositions, scrap paper calculations. She picks it up. The next few pages will be in museums — as precious as DaVinci’s flying machine drawings. The last moments of the Great Red Spot.

“Rachel.”

She looks over at the comm despite herself. The control center glows with an unanswered message. It informs her that, if she ceases all energy expenditure now, they can get to her. Houston-Europa has already deployed a rescue ship. They can intercept in nine hours. She will have to divert all energy to life support. No comm. No measurements. No keeping pace with the Great Red Spot. She would have to let the storm twist away from her.

Looking out the window, Rachel half-believes she can reach out a hand and trail her fingertips in the kaleidoscope of air currents.

The air in the cabin smells charred from the electrical fire and Rachel imagines it’s from the storm outside, filled with lightning and ozone. For a moment it looks like the storm cells swell, trying to touch, trying to merge.

“Listen to me, Rachel. Do what Houston says.” Another blast of angry static she can’t understand. “Let them get to you. Let them save you. Do what they tell you.” He pauses. “Do you remember how the Coast Guard came in?”

Then: After Hurricane Gretel faded out, every wave convinced Rachel they were going to tip over. She held the helm for an hour past the storm’s end. When she let go, the knuckles in her fingers popped. Rachel went to her father, still unconscious on the floor. She put a hand on his chest, shook him. He groaned. She took his pulse — his heart beat, he breathed. Then the radio crackled. She picked it up. Said, “Mayday.”

The men in the uniform strapped her father to a backboard. Took him to the hospital. Took her home. Rather, took her to where her home used to be. They found her mother halfway down the street. Rachel beat them to her — running, splashing through the shallow ocean water. She put a hand on her mother’s chest. Shook her. The water rippled. Her heart didn’t beat, she didn’t breathe. The Coast Guard, a woman with thick black hair the same color as the floodwaters, pulled Rachel away.

Soon: The rescue vessel will approach Rachel’s crippled ship. From the outside, the Iovis appears undamaged. No fire in the thrusters, though. It floats like a buoy.

Then: “It’s all fixed,” her father told her. The boat floated in its dock. New windows. New rigging. A fresh coat of paint. The name Clara a deep black. “She’ll always be with us,” her father said. “Jupiter will be out tonight,” he said. And that night, on the dock, she looked through the telescope, into the heavens — where her mother supposedly had gone. Through the barrel of the scope was the Great Red Spot — right there in the belly of the planet. She felt a similar storm in her own belly.

I’m going to Jupiter, she’d thought.

Now: “You remember looking at Jupiter after Mom?” her dad asks. He is thinking of the same moment in the same moment she thinks it. “I was so grateful for you. Grateful you were there and safe. Grateful you’d saved me. Because you did. You saved both of us.”

The storm is crumbling.

Then: Living on the Clara in the years after her mother’s death taught her to move in close quarters, provided a clear night sky with no light pollution, trained her to handle herself, and drove a wedge between her and her father. They were always together. On top of each other. But never close. Even though she was all he had, and he was all she had.

Her father’s hair turned gray. His hands turned to leather. He shook her hand when he dropped her off at the airport as she headed for her first NASA posting.

Now: With 561 million miles between them, hearing his voice in her ship makes her feel she is still on the Clara in the Gulf of Alaska. She is watching the clouds dissolve. She still can’t take her hands off the wheel.

Lightning jumps from one red cell to another. That’s all that remains of the Great Red Spot: cells. Rachel notes the time in her notebook. Takes a photograph. Sketches what she sees. She notes wind and current speed. Her father says, “They’re going to cut me off — ” a crackle of static, synced perfectly with the lightning shooting across the atmosphere — then — ” — don’t sink here.”

She reaches out and turns off the comm. If there is going to be a break in communication between them, she is the one to control it.

She can concentrate now. The text communications from Houston-Europa still come through. They tell her to power down. They tell her to respond. Affirmative: wait for rescue. Negative: track the end of the storm.

She answers Houston-Europa at 1443 hours. One word.

Soon: The Orpheus, the ship sent to retrieve Major Rachel Cook will shift into docking formation with Rachel’s ship. The ‘claw’ of the rescue ship will reach out and connect with the airlock. The claw’s fine point will press the exterior override, allowing the airlock door to open from the space-side. Captain James Martell will approach and enter the airlock, prying the door open with his gloved hand and closing it behind him.

Now: Rachel arranges her space suit, but half-heartedly. The suit makes her claustrophobic. She doesn’t want to wear it. She doesn’t want to die, but she definitely doesn’t want to die while wearing the suit. So she turns away. Whatever happens, it’s not time for the suit yet.

Soon: Once he enters the airlock, Captain Martell will wait the required decompression time. It will be dark. The lights are off. There is no power. He must pry the interior door the same way he did the exterior.

Then: During her first trip to the international space station, her father decided to travel around the world. As she watched Earth spin below her, she saw hurricanes form and break — in the Pacific, the Atlantic, the Indian. And she hovered over him, unsure if she was ahead or behind.

Once, he’d promised they would go around the world together. Which they did: him on the ocean, her in orbit.

The Clara went down in the middle of a Pacific shipping lane. Her father was rescued. Again.

That was the year of the space station fire. Rachel saved two other astronauts.

One rescued. One rescuing.

She was the one drowning, now, suffocating so far from home..

Soon: Captain Martell will test his communication link. He will exit the airlock and hear the reassuring “Copy” from the Orpheus.

The interior of the Iovis antechamber will be pitch black. The captain will cross himself — hopefully God listens this far away from Earth — and he activates his head lamp. A small lab with some plant experiments underway. A fish in an aquarium. The label says: cutthroat trout. The monstrous, speckled creature will be tapping forlornly at the glass.

Then: They’d discovered the rudder had broken. She could have let go of the wheel. Together, they’d always been at the mercy of the storm.

Soon: The captain will find the door to the main cabin. Burn marks warp the edges. Interior fire. Someone will regret putting Major Rachel Cook on a faulty ship for the first manned orbit of Jupiter. He pulls open the warped hatch.

The light will blind him.

Captain Martell will see everything—Jupiter’s whorls and twirls, the eerie illumination of the dead cabin. No electronics will flash. Lifeless engineering.

He will find Major Rachel Cook drifting through the cabin. Her orange spacesuit the same color as the light streaming in from Jupiter. He will pull her to him, steady her. Check her vitals.

In his headset will come: “Her dad’s hacked through again. He wants to know how Major Cook is doing?”

Captain Martell: “How is he doing that?”

Then: When the Coast Guard saved her father, the sergeant had leaned down and told her they’d gotten her mayday. She told Rachel it was good she’d called, and it was good she kept calling. Too many people called too late.

Soon: Captain Martell will relay that Major Cook had powered down in compliance with Houston-Europa advice at 1450 hours — right after her father’s last illegal transmission. He will report that Major Cook suffered from hypoxemia but, because of the major’s prompt action, she will make a full recovery.

During the twelve-hour recovery mission, the Great Red Spot will dissipate. However, because of rapidly shifting conditions during the Jupiter-day rotation, by the time Orpheus docks at Houston-Europa, the Great Red Spot will spin, once again, to life. Rachel will wake, calm, steady. After the storms, she will breathe the soft hush filling the space between the stars.

End

Great story! I like how you structured it, jumping between past, present, and future. That’s a cool thought that the Great Red Spot that we all learned about in school could just dissipate someday, and I love the idea of Rachel having to choose between her life and observing this incredible event. Also, that was a cool detail the rudder broke, that the entire time Rachel was trying to keep that boat stable, the wheel wasn’t doing anything.

I’m curious why you decided to have the Great Red Spot reform by the end of the story. I was expecting it to fully dissipate to symbolize the storm inside of her calming/her gaining inner peace. Great story! Thanks for writing it!