Remix of photos by Stephen Leonardi and Baghaei photography

Hard Points

by R. Keelan

“Lockdown initiated,” Alice’s preternaturally calm AI voice announced. “Virate presence detected with 98% confidence.”

I scrambled to my feet, pulled by hysteresis hinges in my suit’s exoskeletal loadout. “Here?” I swept the muzzle of my rifle around the room. “Where?”

“The Virate signature was detected in the high security clinical lab.”

I bounded for the door. “Who’s in there?”

“No service badges detected in the lab,” Alice said.

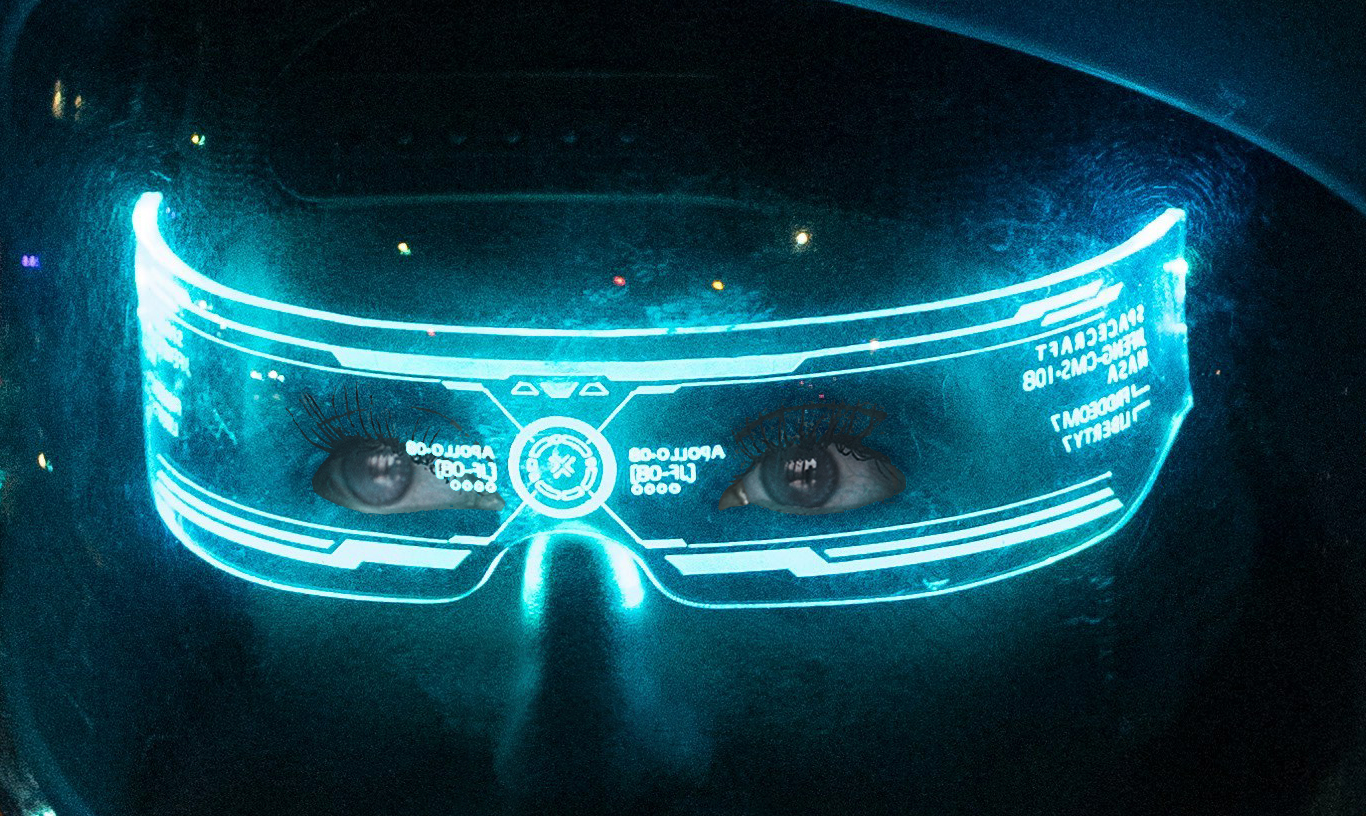

What the hell? I asked Alice to show a route to the lab on my viewplate and ran, muscle amps in my loadout propelling me down the hallway at inhuman speed. On my helmet’s heads-up display, a glowing, pale blue arrow indicated a left turn at the end of the hallway.

“Alice, seal all vacuum hatches except those between my position and the lab, then switch every compartment over to local life support.” Best to limit airflow so that the spores wouldn’t spread—

“Unable to comply,” Alice said. “We are not authorized to perform that operation.”

Jesus—”What access do we have?”

Alice considered that for a moment. “None.”

It was the middle of the night, and I’d only arrived earlier that day, but I was the ranking officer of the Terran Protectorate Civil Guard assigned to this station. I should have access to every function. Was someone late adding me atop the security roster? Or had station administrator Clay fucked me? “Who’s on duty?”

“No duty assigned for this watch.”

“Is anyone online?”

“No other service badges are currently connected to a hard point suit.”

Christ. What a cock-up. This was a high-security installation during wartime. How could none of my Guards be online?

I slowed to a walk as I approached the lab. Both sides of the airlock were open. From my vantage in the hallway, I could see a bank of white, metal storage lockers and little else—the lab extended away behind them.

Alice had been unable to ascertain the nature of the Virate signature, but to reach a 98% confidence level, there must be at least one drone: an organism—presumably human, given the station’s demographics—infected by a Viri parasite.

I stepped through the airlock, pivoting to clear the blind corner on my left. The lab ended just a couple metres in that direction, terminated by two tables shoved into a corner at right angles. Above them, an infographic summarized the protocols of a biosafety level 5 laboratory. The rest of the lab was accessible by a gap between the storage lockers and the far wall.

The left side of my heads-up display had a full panel of vital signs fed by smart sensors inside my hardpoints. The readout snapped into focus as my eyes flicked over to them, darkening to semi-opaque. My heart rate was elevated; my cortisol level spiked as I squeezed through the gap between the storage lockers and the wall.

Beyond the lockers, Dr. Khalid crouched over a workstation set against the far wall, wearing a modest nightgown and a midnight-blue hijab. That was a violation of the safety protocols for any lab—was she the Virate presence? A drone wouldn’t have bothered with religious attire, but she might have put on her hijab when she woke and succumbed to the infestation later.

Alice had designated her as a potential hostile, but I pointed my rifle at the floor a metre away from her feet. If she was a drone, I’d just have to neutralize her some other way. “Dr. Khalid?”

She turned to face me, rapid-fire Arabic tumbling from her lips. A moment later, Alice whispered a translation, perfectly reproducing the strain in Dr. Khalid’s voice. “It’s just a drill. My subjects are all in the holding chamber, and—”

“Sound off, please,” I ordered in English.

Dr. Khalid’s eyes flicked down to the muzzle of my rifle then back up to my face, her expression opaque. “Dr. Zahra Idris Khalid, Research Director, Chaos Station, Hawaiki star system” she said, still in Arabic.

“Thank you,” I said, but didn’t lower my weapon. “Now, do it electronically.”

“I don’t have my badge,” Dr Khalid said apologetically. “I left it in my room.”

My service badge was plugged in to a hard point socket on my chest. I disengaged it and tossed it to her underhanded. “Use mine.”

Dr. Khalid held the badge against the back of her neck.

“Alice, a brain scan of Dr. Khalid, please.”

I waited while my badge monitored nerve impulses travelling through her spinal cord. I watched her intently at first, then flushed and looked away. Perhaps the nightgown wasn’t as modest as I’d thought.

“Scan complete,” Alice said. “Result: negative.”

Dr. Khalid couldn’t hear the words, but relief must have shown on my face. “Satisfied?” she asked, a hint of challenge in her voice.

I slung my rifle and turned away, embarrassed. “You should be wearing your hardpoints,” I said. “With a life support module. What if I’d depressurized the lab?”

“That would have been rash.”

“Not if there were Viri spores in the air,” I said, ostentatiously peering into the lab’s transparsteel holding chamber. There were twelve tables in an austere, colourless room, each with a body strapped to it. “And close the airlock behind you next time.”

“You’re fortunate that was only a drill, Captain Ramsay,” Administrator Clay said in English. It was a human facsimile, a Manifestation of the Transcendental known as Death. It had thick, glossy hair the colour of ash, a pallid complexion, and shiny metallic irises. All of the Transcendentals liked to be coy about their true natures. I believed they were members of a highly advanced alien race, but many religious sects believed they were aspects of God, a notion the Transcendentals were careful never to contradict. They all adopted names from our languages, abstractions like Wisdom and Valour, rather than use their own; and sent Manifestations made in our image rather than come among us in their own forms. But Death was unique in adopting a negatively-coded name and being so cavalier with phenotypes.

Clay was especially striking juxtaposed with the surrounding normalcy. Its veneered particle board desk could have come from any office anywhere in the Protectorate. Off-white wall panels concealed the asteroid station’s metal bulkheads, and sunlight-calibrated LED panels shone down on indestructible, ruggedized carpet.

I tipped back my chair and propped my feet on Clay’s desk. I’d parked my loadout in my quarters before answering Clay’s summons but hadn’t changed out of my hardpoints. The connectors—the eponymous hard points to attach a loadout—registered reassuringly as stiff points amidst the suit’s otherwise-flexible ballistic fibre.

I always wore my hardpoints.

“That was the first drill you’ve ever had, wasn’t it?” I said.

Clay ignored my provocation. “You didn’t follow protocol—”

“You didn’t have any Guards on duty!”

“Hendelman was the captain—”

“You liked Hendelman—”

“Cease interrupting me, human!” Clay’s voice rose in volume to compensate a drop in octaves, but its expression didn’t change.

I smirked. Most Transcendentals—and their Manifestations—were quite good at maintaining a façade of otherworldly detachment. Death was different.

“Station protocol dictates,” Clay said, “that when a Virate presence is detected with greater than fifty percent confidence, your first priority is my preservation. I possess a full back-up of the station’s records, some of which, at any given time, will not yet have been sent to Death proper. Next time, I expect you to seek me out.”

“Does the protocol say anything about the rest of the crew?” I asked sardonically.

“After I’ve been secured, the Guard’s usual policies and procedures take effect.”

“And what are those?” I asked.

“I expected you’d be familiar with them”—Clay paused while the cache misses piled up—”but I can recite them if you’d like.”

I stood to leave. “You should have consulted them before holding the drill.”

Outside Clay’s office, Dr. Khalid and Lieutenant Crecy were waiting in the white, sterile hallway. Dr. Khalid had changed into a stretchy, ankle-length dress. Crecy was wearing the Guard’s brown working uniform.

“It was a drill,” I said in English. I could distinguish each of the Protectorate’s twelve official languages, but English was the only with which I was proficient.

“Dieu merci!” Crecy said, relief pouring off her round, cherubic face.

Dr. Khalid smiled knowingly.

I fixed Crecy with a humourless stare. She had razor short, sandy brown hair, and fair skin prone to flushing. “I want to know why I was the first to respond,” I said. “Who was supposed to be on duty?”

“I—I’d have to check the roster,” Crecy said in French, which Alice dutifully translated, stammer and all.

“That was a trick question,” I said. “No one was on duty because none was assigned. Apparently, this is some kind of furlough station.”

Crecy didn’t respond. She couldn’t. I’d been assigned to Chaos Station to replace Captain Hendelman, her former commanding officer. Crecy was probably too loyal to throw Hendelman under the bus, but clearly unable to defend her actions.

“Perhaps you’d care to fix that, Lieutenant,” I said.

“Yes, sir—of course, sir.” Crecy turned and hurried away, pulling her badge off her uniform and feigning deep interest in its display panel.

“And I want the name of every Guard that can’t produce their hardpoints inside five minutes,” I called after her. “If the Virate attacks, that’s all the warning we’ll have!”

“The duty roster is Hendelman’s fault,” Dr. Khalid said. She at least had the grace to wait until Crecy was out of earshot before saying it.

“If the outbreak had been real and we’d all died, not being at fault wouldn’t be much consolation for Crecy,” I said. “Better for her to proactively fix Hendelman’s mistakes while hating my guts than to wait for me to discover them on my own.”

Dr. Khalid looked skeptical still, so I changed the subject. “How did you know it was a drill?” I asked. “You said your subjects were still in containment, but you only learned that after you checked the lab.”

Dr. Khalid pursed her lips. “Will you go easier on Crecy if I tell you?”

“I’ll be exactly as hard on Crecy as she needs me to be,” I said, “but I might be less of an ass about it.”

Dr. Khalid laughed involuntarily. “I checked for Administrator Clay’s location,” she said. “It was stationary in its office, but if the lockdown had been real, it would have taken action, seeking out Guards or moving towards the lifeboats.”

The next morning, Dr. Khalid—Zahra, she insisted—intercepted me on my way to breakfast. She had a strong, aquiline nose, and pretty brown eyes. She placed a hand on the small of my back, guiding me towards the asteroid station’s north. “What do you know about what we do here?” she asked in Arabic.

We had no language in common, so I replied in English. “You’re working on a new Viri vaccine.”

“And what’s different about it?”

My last posting had been majority Swahili, so I was already accustomed to the unique ebb and flow of translation-assisted conversation, adept at picking Alice’s translated English syllables from among Zahra’s Arabic ones.

“It doesn’t work,” I said. “Our current vaccines are at least partially effective.”

I looked over to gauge Zahra’s reaction, but she just smiled. “I see you haven’t read any of my progress reports. In our latest trial, 80% of subjects resisted infestation.”

“Eighty percent of rats,” I said. “Their brains are simpler. Easier to inoculate.”

“The latest trial was chimps—you must have passed the report while in transit.”

We came to a halt in front of an airlock portal, the high security lab from the night before. Zahra reached for the control pad next to the door.

My neck itched. “Why don’t we go to a conference room, and you tell me how your vaccine works?” Most people only wore their hardpoints when they had to, finding the skin-tight suit uncomfortable or immodest. I’d lived in mine for three months on Summerland, even when hiding up in the mountains where the spores didn’t fare so well. I preferred it now to the Guard’s working uniform. But hardpoints alone wouldn’t protect me from Viri spores; for that, I’d need my loadout’s helmet.

Zahra moved her hand to my elbow. “Don’t you want to see what safety measures we have in place?”

“Okay, but let me get my loadout first.”

Zahra’s smile deepened. “Don’t tell me you’re afraid of the Viri! Didn’t you survive Summerland?”

One of Earth’s thirteen colony worlds, Summerland had been overrun by the Virate the year before. I’d run my loadout from the first, savage day of the Virate attack until several days after finally going orbital. I never slept without its hermetic seal and recycled air anymore. At first, I’d fixated on the drones, thinking I could somehow undo the infestation by killing my former friends and acquaintances. But in time, I’d learned it was the spores that were the true threat; I’d survived Summerland because I’d been afraid of them, because I’d never taken chances. But that didn’t express the insouciance that had been my refuge this past year, so I plastered a smirk on my face and waited.

Zahra squeezed my elbow. “Let’s go to the mess,” she said.

Chaos Station—Death had named it—was an asteroid in far orbit around Hawaiki’s sun, out near the Terminal Shock. It was operated under the auspices of the Terran Protectorate’s defense research agency. Other than Clay, everyone on-station was either a soldier or a civilian employee of the agency, so the mess didn’t charge for meals.

We sat in an aggressively clean booth in a far corner, away from the handful of other patrons. The olfactory twitch of disinfectant lingered in the air, off-gassing from the vinyl upholstery of our seats.

Zahra explained that she and her team were working on a novel Viri vaccine to complement or replace the vaccine currently standard throughout the Protectorate. Since it had proven effective on chimps, she had started cadaver trials. Partially brain-dead corpses had been shipped to the facility—on life support to keep the cerebellum and brainstem alive—and exposed to Viri spores to see how well the new vaccine protected human brains.

“How will you know if the vaccine is working?” I asked. “Behavioural fingerprinting won’t work because the cadavers are just lying there, and if they’re infested, those cadavers will become spore factories.”

Zahra leaned towards me. “We’ll be monitoring nerve impulses daily for signs of infestation.”

“The cerebrum’s dead, the nerve impulses will be way out of distribution to start with.”

“Clay has developed an algorithm to compensate for that.”

“If containment in that lab fails at the wrong time,” I said, “the entire station could be infested in a single generation. R-zero would be effectively infinite.”

Zahra nodded in approval of my point. “The Viri holding chambers are on a separate life support system and kept at negative pressure relative to the rest of the facility. All three systems would have to fail at the same time to put us in any danger.”

I made a noncommittal sound. Zahra’s confidence was reassuring, but I didn’t want her to know that.

The conversation lulled for a moment while Zahra looked down at the table, then she looked up into my eyes. “The attack on Summerland must have been very difficult for you,” she said. “All those people lost to the Virate…”

I so enjoyed listening to Zahra talk that I almost didn’t recognize the question implicit in her statement. “Lots of things are difficult,” I said. “Leaving home was difficult. Officer candidate school was difficult. Summerland was…”

Summerland was a discontinuity, a break in the timeline of my life, impossible to evaluate. “I was just trying to survive. Everything I did, every drone I shot, was because I had no other choice.” For a moment, I was back on Summerland, foraging in that grocery store… No other choice, I repeated firmly to myself.

“I’m sorry for what I said earlier.” Zahra brushed the back my hand with a finger. “It was insensitive.”

I began to pull my hands in towards myself, then stopped. “It’s fine,” I said. “I’m not post-traumatic or anything. I just don’t like talking about it.”

I asked Zahra to have lunch with me again the next day, to help familiarize me with the station’s personnel and day-to-day operations, an excuse she found quite droll. When Zahra invited me to her quarters for dinner the day after, I hesitated, saying we should wait until our duty stations diverged. But Zahra had laughed and pointed out that she was a civilian who didn’t have a duty station, and I’d let her persuade me.

Clay held a drill every day of the first week, timed either for the middle of the night or shift changeover. In the best performance we put up, half my Guards got to their loadouts before Clay ruled them infested. But they were cut off from the armoury and its heavy weaponry, so they decided to retreat to the lifeboats while I raged from the sidelines. Guards with combat loadouts should be perfectly willing to engage drones up to stage three in a melee, even if they were otherwise unarmed, because only stage four drones had the mental capacity to use modern weaponry.

Or care for children, I thought bleakly. I was in the Sacred Space, a non-denominational prayer room to which Clay relegated me after I was invariably “infested.” Unlike the rest of the station, the Sacred Space was oddly gloomy, with dark blue carpet, faux-wood paneling on the walls, and ultra-low temperature lighting reminiscent of candles. Perhaps it was comforting to people who routinely spent time praying.

“How did we do?” Zahra asked behind me. A moment later, her arms encircled my waist in a brief hug.

“Our performance was embarrassing,” I said, “which I suppose is better than the outright humiliation from when we started.” I turned to return Zahra’s embrace. “How’s your research?”

“No sign of Viri infestation so far,” Zahra said. “It’s still too soon to draw any conclusions, but if anything, the vaccine seems more effective for humans than lower-order lifeforms. When Clay suggested collaborating on this research, I was taken aback. Transcendental technology is so far beyond us—the ballistic fibre they use for hard point suits is just beyond our technological horizon, but our best understanding of physics still insists that FTL travel is impossible, even with their drives built into our ships.”

Zahra began pacing, becoming too animated to stand still as she spoke. “Death thinks human physiology is especially suited to vaccination, but the optics of studying human Viri-resistance on its own are obviously so bad that even Death balked, so it needed a partner. Meanwhile, I was already here, and had done my dissertation on—What? Why are you looking at me like that?”

“I like the way you talk so matter-of-factly about the Viri,” I said. “Like it’s just another phenomenon to be understood.”

Zahra laughed a little, probably thought I was teasing, but that was okay. I felt braver and calmer when I was with her.

“Lockdown initiated. Virate presence detected with 95% confidence.”

The seventh in three weeks. “What time is it?” I asked muzzily.

“Zero one-hundred hours,” Alice said in my helmet’s speakers.

Clay had fought every change I’d attempted to institute, arguing that increased drills were sufficient. It wouldn’t even consent to biopsying Zahra’s Viri-resistant animal test subjects. They hadn’t displayed behavioural symptoms. That was enough.

“Where’s Zahra?” My duty was to Administrator Clay before Research Director Khalid, but Zahra with the pretty brown eyes came before either.

“Dr. Khalid is in the high security clinical lab.”

“And Clay?”

“Administrator Clay is in the high security clinical lab.”

I was instantly on my feet and reaching for the door’s control pad. Clay had always been in its office for prior drills, no matter the confidence level.

“How are my seals?” Sudden fear had turned my voice jagged.

A row of icons blinked onto my viewplate, all green, and the constriction of my chest eased a notch.

“Where’s the Virate signature?” My voice was under control now. I’d always run cool on Summerland.

I flashed back, unbidden, to my final day there: raiding a grocery store just before the Hiveship pulled us out. I thought the city was going to be a hellscape of crumbling buildings and drones feasting on corpses, but it was tidy, orderly. There had been two drones outside the grocery store, obviously parents, with an infant that couldn’t have been more than a month old. But the city had fallen three months before, so that baby had been born to drones. From their reaction, they’d loved and cherished and feared for its safety just the way humans would have.

Alice’s answer to my question pulled me out of the memory. “The primary signature is on Deck Five, E corridor. Secondary signatures on all other decks.”

Primary? Jesus.

I made an intricate gesture with my left hand, switching to broadcomm. “This is Captain James Ramsay. All personnel, sound off.”

A string of French words came first, Lieutenant Crecy’s response, calm and collected.

Shaky Arabic followed. “Zah—Dr. Khalid here.”

“I’m with Dr. Khalid,” Clay said, also in Arabic. “We’re headed for the lifeboats.”

I waited, but no one else sounded off.

“We’ll hold position until one of you arrives,” Clay said a moment later.

Chaos Station’s crew complement had been 146.

I switched off broadcomm—”Alice, plot me a route to Clay and Zahra’s location”—then re-enabled it: “Crecy, where are you?”

“Heading for the armoury to grab a loadout.”

That was deck five. “Watch out. AI reports a Virate mass in your area.”

I disengaged my rifle’s safety, then activated the door with my gauntlet-encased pinky. There were two drones outside my quarters, at the far end of the hallway. They were the first I’d seen since Summerland. Both were stalkers: stage three drones with full control of the host’s motor control and sensory perception. The drones turned and sprinted towards me. I sighted down my rifle’s scope, thinking of my small arms instructor’s admonition to always put a drone out of its misery. But he hadn’t known what became of drones any more than I had, and thanks to me, he’d never found out: I’d obeyed his admonition after he succumbed to the infestation.

The drones were unarmed, unable to hurt me in my loadout. I squeezed my eyes shut but couldn’t bring myself to fire. The first stalker slammed into me at full speed, knocking me backwards. When the second one hit, I toppled over, and my rifle went skittering away. The male drone sat on my chest and scrabbled at my viewplate. The other was on my legs, but I couldn’t see what she was doing.

I’d never panicked on Summerland, but my breath was loud and heavy in my ears, and a pulsing icon on my view plate indicated tachycardia. Now I knew I didn’t have to kill anyone, just get away. I rolled onto my stomach, dislodging the two drones, then crawled over to my rifle and climbed to my feet. The male jumped on me and I batted him away. Propelled by my loadout’s muscle amps, he crunched into the wall and lay still.

The female drone backed away, cautious now.

I turned and ran.

Along the station’s sleek, white corridors, a handful more drones reached for me with grasping fingers. I bowled right over them, slowing just enough to avoid causing serious injury.

When I reached the high security clinical lab, I found Clay sprawled just inside the airlock, its silver eyes wide and vacant. Zahra was crouched over it, wearing a civilian deep space loadout.

“What happened?” I asked.

“I—I don’t know,” Zahra said. “It just collapsed all of a sudden.”

For a moment I just stared, at a loss. Clay’s safety was supposed to be my first priority. I pressed my badge against its forehead—maybe it wasn’t actually dead. “Scan it.”

“No brain activity,” Alice said.

Zahra looked at me questioningly.

“It’s dead,” I said. In life, Clay had always seemed more than human. In death, it looked as fragile and exquisite as any of us.

“But—how?”

“Manifestations are designed to self-terminate if Viri spores reach critical mass, to make sure the Virate never gets control of one,” I said, repeating a fragment from a far-off training brief.

Zahra looked down at Clay. I couldn’t see her face.

“How are your seals?” I asked. “When did you suit up?”

“As soon as I woke,” Zahra said. “In my quarters, like you told me.”

“The Virate mass is approaching our position,” Alice said.

“We have to go.” I stepped out of the airlock, and there was Crecy, raising her rifle to firing position—

I jerked back as a round screamed past my view plate.

I toggled firing modes and launched a grenade into the corridor at an oblique angle. I sent two more careening after it, firing blind.

“Zahra?”

“Yes?”

She was right behind me.

“Crecy’s infested. When I step into the corridor, I want you to follow. Go north. I’ll cover you.”

I counted off three muted whumps, then stepped out, gun raised. I was relieved to see that the corridor, blackened and scarred, was empty. Crecy had survived.

Zahra bolted past me, and I walked backwards after her.

Crecy peeked around the corner; I fired over her head.

She stuck just her rifle out next, firing wildly.

I fought the urge to crouch, instead lobbing grenades down the hallway at a steady pace, until Alice informed me that Zahra had rounded the corner. Only one to keep safe, and the most precious.

Zahra went to the cockpit of the small, barely FTL-capable lifeboat umbilically docked to the asteroid’s north pole while I watched for boarders. I knelt in the airlock, anxiously wondering what I’d actually do if a drone approached.

None did, and soon a slight tremor announced the boat’s separation from Chaos Station.

I half sat, half collapsed onto the bench, resting against the bulkhead.

“Were the drones on Summerland like that?” Zahra had returned from the cockpit, standing just outside the airlock.

I set my rifle down on the bench beside me. “Not like that,” I said. “That was a swarm, bent on spreading the infestation at any cost. On Summerland, entire cities were infested. They became colonies, networks of drones that resumed their prior patterns of life. It makes sense, right? The Virate had a city full of human hosts to keep alive. The best way to do that was to run it like we would have, so that’s what the Virate did.”

Zahra listened quietly, then disappeared deeper into the lifeboat. I kept picturing Clay, terminated by its own body.

I tried to picture Zahra instead, dark eyes peering out of her squat, angular helmet. She must have worn it all night, like me, to avoid being exposed to the spores that had infested Clay.

But she said she’d suited up after she woke.

I reached instinctively for my rifle. “Why do you ask about the drones?” I asked. Our suits were comm-linked, but I went to find Zahra anyway. I had to be sure.

Zahra was standing on the far side of the next compartment.

“I just wondered what it’d be like,” Zahra said.

I held my rifle slanted across my chest, muzzle pointed at the deck. “For the others, you mean. The ones we left behind.”

Zahra unclipped her badge and pressed it against the back of her neck, her brown eyes mournful.

I said, “Alice, give me the result of Zahra’s scan.”

“Test still in progress.”

I toggled my rifle’s round selector back and forth. “Now?”

“Test still in progress.”

Jesus. I glanced at Zahra’s face, but she was watching me, so I looked away.

“Scan complete,” Alice said at last. “Result: positive.”

I scuttled away, raising my rifle to firing position, but the scan had to be wrong. A stage four drone might impersonate her former host, as Crecy had done, but she wouldn’t just stand there. She wouldn’t look so heartbroken.

“Your badge must be damaged,” I said. “Or interference—”

Zahra jerked her head. “I put on my hardpoints after the alarm, like everyone else.”

“But you’re still you!”

“I vaccinated myself, James, as soon as I realized the lockdown was real.”

“Then—the vaccine worked?”

“It doesn’t halt the infestation, it just—I don’t know, neutralizes it somehow. That’s why Clay never let us autopsy any of the subjects, why it was so cagey about security. All of my ‘resistant’ subjects were actually carriers to start with. That’s where the infestation came from.”

“Okay, but if you stay in your loadout, and I stay in mine, we’ll be fine. Once we’re picked up, the doctors will—”

“What? Let me go free? Put me in quarantine? Or will they put me in the incinerator to keep me from spreading the infestation?”

Zahra stepped towards me, and I stepped back.

“Where are you going?” I asked.

Zahra took another step, bringing her to the airlock.

“Stop!”

Zahra ignored me.

“You’re just going to kill yourself,” I said. “Why not come back and at least try—”

“It’s not suicide.” Zahra’s poise slipped, her voice skittering over melodic Arabic syllables. “My loadout is vacuum rated. There are other lifeboats on Chaos station. The drones will recognize me as one of their own.”

“What if they don’t?” I pressed the butt of my rifle into the pocket of my shoulder. “What if you succumb without more treatment?”

“I’ll continue my research.” Zahra closed the ship-side hatch. “Maybe I can turn the vaccine into a cure.”

I bent my head to the rifle, sighting through the scope, as if there was any fucking point. “I’m ordering you to step out of the airlock. Get back in here.”

Her hand moved to the control pad.

“Zahra, please, don’t do this!”

“I’m sorry, James.” She jerked backwards out of the airlock.

I stared, disbelieving, then crumpled to the floor, listening to the faint hum of my loadout’s rebreather unit, cradling my rifle in my arms.

After a time, Alice clicked gently to indicate that Zahra’s connection had dropped. She was out of range. My rifle lay next to me. Along with my loadout, it had been a constant companion since Summerland.

I climbed to my feet, stooped to pick up the rifle, then hurled it across the lifeboat.

END

Leave A Comment